Encoding Relative Positions with RoPE

The Transformer network is position-agnostic. In other words, it doesn't care about the order of the input sequence. You can easily see the reason from the equation of the Attention mechanism (more specifically, how attention weights are calculated), the primary component in the Transformer:

$$ \text{softmax}\left(\frac{\mathbf{q}_m^T \mathbf{k}_n}{\sqrt{|D|}}\right) $$

It only depends on the content of the queries and keys, not where they are positioned in a sequence. But in many cases, we want the network to be able to distinguish the positions of tokens in a sequence. For example, you certainly don't want the network to interpret the sentence "Jack beats John" exactly the same as "John beats Jack".

Thus the idea of positional encoding is born: we can explicitly include information about positions of queries/keys in their content. The network is certainly able to distinguish "1-Jack 2-beats 3-John" from "1-John 2-beats 3-Jack" even when it cannot directly access positional information.

Vanilla Positional Encoding (PE)

Formulation

The original Transformer paper recognized this limitation in position-awareness and introduced the vanilla positional encoding (PE for short). For an input token at position $pos$, PE is a multi-dimensional vector where the odd and even dimensions are calculated as follows.

$$ PE_{(pos,2i)} = \sin(pos/10000^{2i/d_{\text{model}}}) $$

$$ PE_{(pos,2i+1)} = \cos(pos/10000^{2i/d_{\text{model}}}) $$

This vector is then directly added to the token embedding vector.

To build intuition for how PE works, consider an analogy to old-fashioned electricity meters or car odometers. Imagine a mechanical meter with multiple rotating wheels. The rightmost wheel rotates the fastest, completing a full rotation for each unit of position. The next wheel rotates slower, completing a rotation every 10 units. The wheel to its left rotates even slower, once per 100 units, and so on. Each wheel to the left rotates at an increasingly slower rate than the one before it.

In the vanilla PE formulation, different dimensions correspond to these different "wheels" rotating at different frequencies determined by $10000^{2i/d_{\text{model}}}$. The sine and cosine functions encode the continuous rotation angle of each wheel. This multi-scale representation allows the model to capture both fine-grained positional differences (nearby tokens) and coarse-grained ones (distant tokens) simultaneously. Just as you can read the exact count from an odometer by looking at all wheels together, the model can determine relative positions by examining the patterns across all PE dimensions. It's worth noting that PE shares a very similar idea with Fourier Features.

Relative Position Information

Computing the dot-product of two PE vectors reveals that the result only depends on the difference of position indices (in other words, relative positions):

$$ PE_i \cdot PE_j = \sum_k \cos(\theta_k (j-i)) $$

Where $\theta_k$ is the frequency. Since dot-product is the primary way different tokens interact with each other in the Attention mechanism, the Transformer should be able to interpret the relative positions between tokens. However, relative position information is not the only thing the Transformer receives. Since PE vectors are added to token embedding vectors, the absolute positions are hardcoded to each token. This causes problems when you try to extend a Transformer to sequences longer than the longest sequence it saw during training. Intuitively, if a network only sees absolute position indices from 1 to 100 during training, it will have no idea what to do when it receives a position index of 500 during inference.

Rotary Position Embedding (RoPE)

RoPE is proposed to achieve one goal: let the Transformer only interpret relative position information, while maintaining the benefits of PE (that is, it is a non-learning encoding, adding very little computational overhead, and does not require modifying the Attention mechanism).

Remember that the dot-product of PE vectors is already relative, the problem being they are first added to token embedding vectors. RoPE is designed so that the dot-product of the query and key vectors are purely relative, formally:

$$ \langle f_q(\mathbf{x}_m, m), f_k(\mathbf{x}_n, n) \rangle = g(\mathbf{x}_m, \mathbf{x}_n, m - n). $$

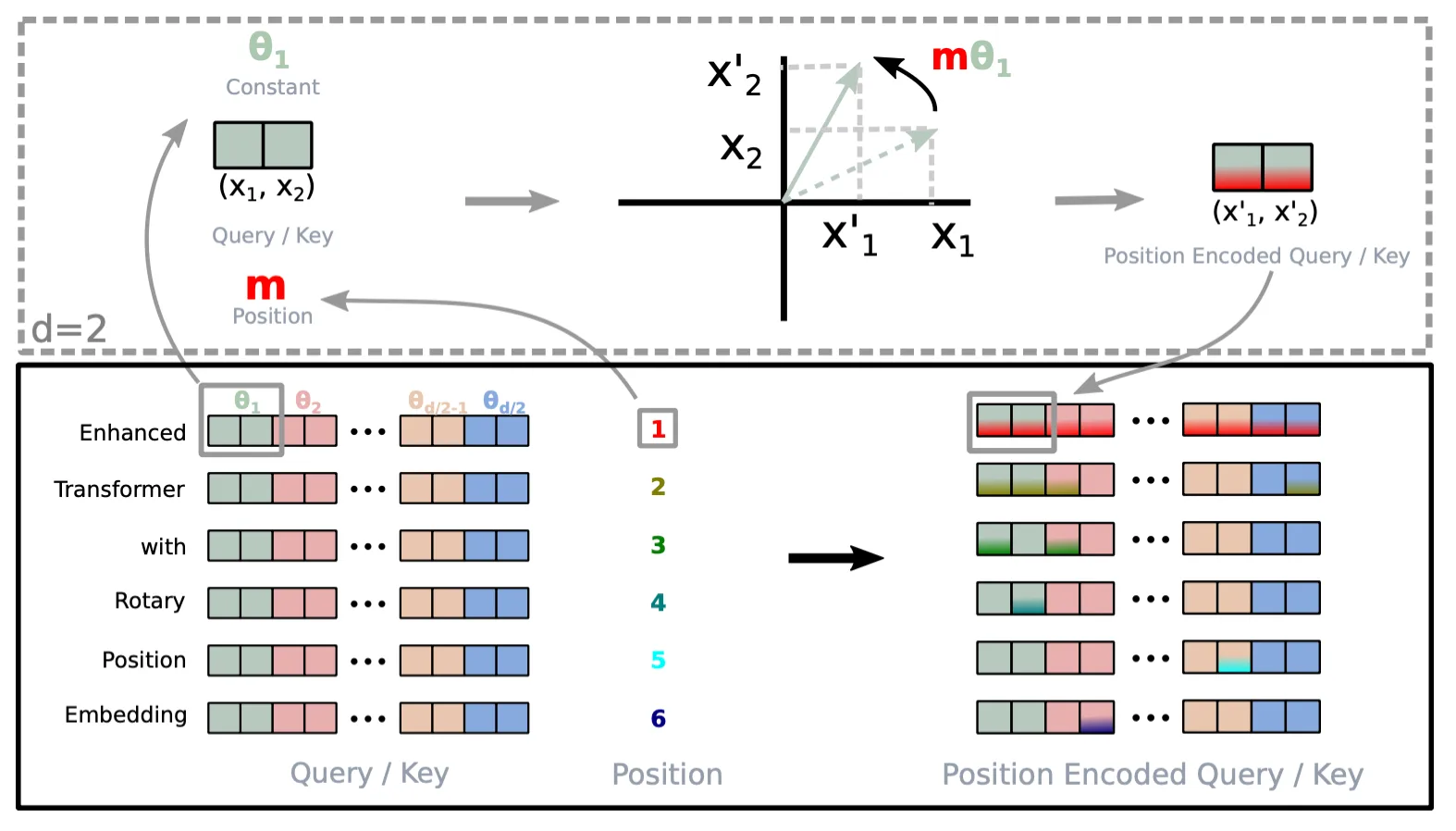

And a query/key vector under RoPE is calculated as follows, assuming the vector is 2-dimensional.

$$f_{\{q,k\}}(\mathbf{x}_m, m) = \begin{pmatrix} \cos m\theta & -\sin m\theta \\ \sin m\theta & \cos m\theta \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} W_{\{q,k\}}^{(11)} & W_{\{q,k\}}^{(12)} \\ W_{\{q,k\}}^{(21)} & W_{\{q,k\}}^{(22)} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x_m^{(1)} \\ x_m^{(2)} \end{pmatrix}$$This essentially rotates the input token embedding vector with a certain angle determined by the pre-defined frequency and the token's position index. The dot-product of two rotated vectors depends on their angle difference, which is determined by their relative positions, making the interaction purely relative. You can also understand RoPE with the rotating meters analogy above, since it is literally rotating vectors as if they were meter hands. After receiving those vectors, the Transformer is like an electrician, who only cares about the relative angle difference of meter hands between two reads, rather than the absolute positions of the meter hands at each read.

RoPE can be extended to arbitrary $d$ dimensions, by dividing the vector space into multiple 2-dimensional sub-spaces.

$$f_{\{q,k\}}(\mathbf{x}_m, m) = \begin{pmatrix} \cos m\theta_1 & -\sin m\theta_1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \sin m\theta_1 & \cos m\theta_1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \cos m\theta_2 & -\sin m\theta_2 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \sin m\theta_2 & \cos m\theta_2 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & \cos m\theta_{d/2} & -\sin m\theta_{d/2} \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & \sin m\theta_{d/2} & \cos m\theta_{d/2} \end{pmatrix} \mathbf{W}_{\{q,k\}} \mathbf{x}_m$$The frequency $\theta_i$ is gradually decreased from $\theta_1$ to $\theta_{d/2}$, just like PE. This means the beginning dimensions have higher frequencies, thus rotate faster; the ending dimensions have lower frequencies, thus rotate slower.

As a purely relative positional encoding, RoPE inherently improves the Transformer's generalizability to sequences longer than the longest training sequence. For example, even if the Transformer only saw sequences no longer than 100 tokens during training, it at least understands the concept of relative distances up to 100. This allows it to reason about the relationship between two tokens at positions 500 and 550 during inference, since their relative distance (50) falls within the trained range.

Extending RoPE

Absolute positions are essentially relative positions with regard to the first position. Thus, RoPE is not totally free from the limitation that prevents PE from generalizing to sequences longer than those saw during training. In other words, if the network only understands relative position differences no longer than 100 through training, it won't be able to fetch a context longer than 100 tokens away during inference, which is still a problem especially for large language models.

Since RoPE's first mainstream adoption in LLaMA, over the years lots of efforts in extending RoPE to context length beyond training emerged. Ideally we want to extend RoPE without fine-tuning the Transformer, or at least only fine-tune with much smaller training set and much less epoches than training.

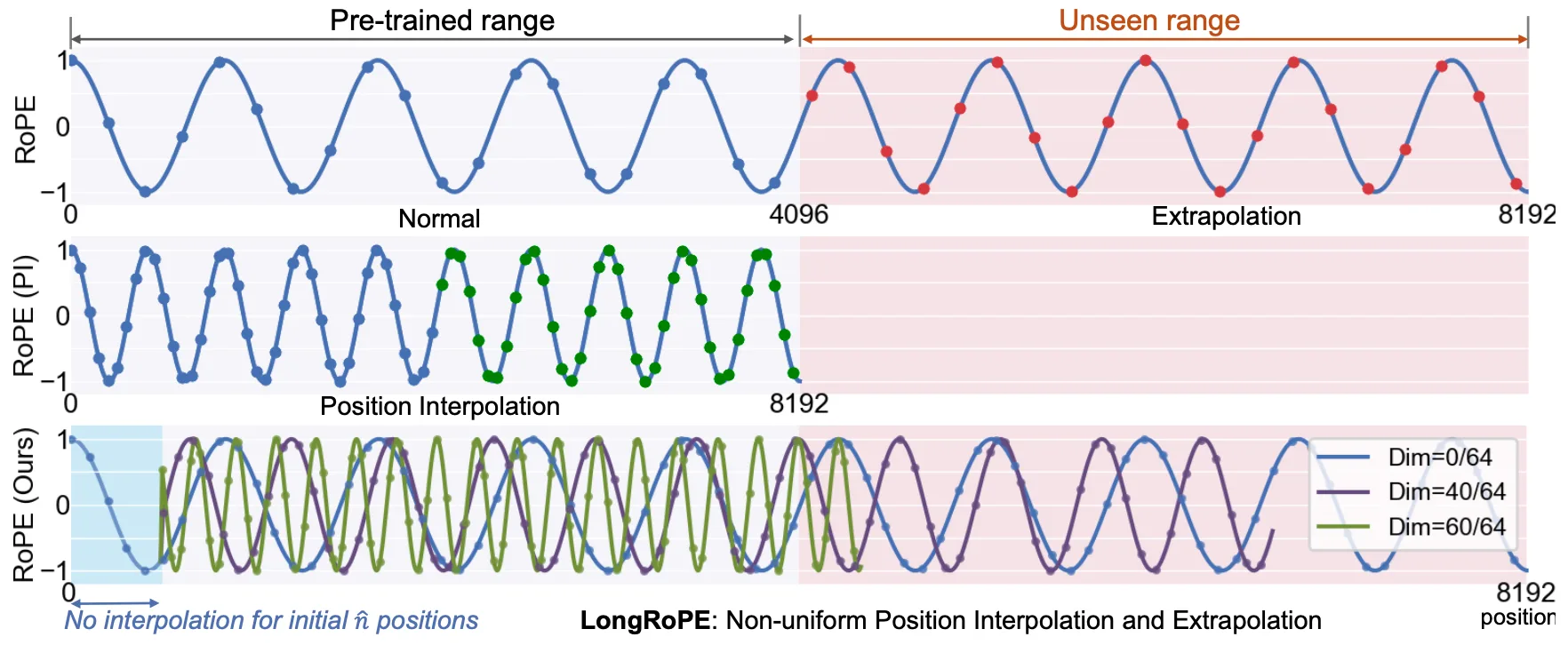

Positional Interpolation (PI)

PI is a straightforward extension of RoPE: if the network can only interpret relative position differences (context) up to a certain length, then we simply squeeze the target extended context during inference to fit that length. Formally, if $L$ is the training context length and we want to extend it to $L'$ during inference, PI scales every input position index $m$ to $\frac{L}{L'}m$.

You can easily see the limitation of PI: the network cannot directly understand the compressed relative positions without fine-tuning. For example, if $L'=2L$, then a relative position of 2 will be compressed to 1 by the scaling, and a relative position of 1 becomes 0.5, which the network never encountered during training. Thus, fine-tuning is necessary for PI to work effectively.

Yet Another RoPE Extension (YaRN)

YaRN is the result of multiple "informal" techniques proposed on Reddit and GitHub (NTK-aware interpolation and NTK-by-parts interpolation) that were later formalized in a research paper.

The intuition is to find a more "intelligent" way to implement positional interpolation. In real-world applications of large language models, contexts positioned farther away from the current position (i.e., a larger relative position difference) are usually less important than contexts positioned closer (i.e., a smaller relative position difference). Thus, even if interpolating RoPE will inevitably degrade the Transformer's performance, we should minimize degradation to smaller relative positions.

YaRN achieves this by recognizing that different dimensions of RoPE serve different purposes. Remember the odometer analogy where each wheel rotates at different speeds? The fast-rotating wheels (high frequencies) are crucial for distinguishing nearby tokens, while the slow-rotating wheels (low frequencies) encode long-range positions. PI's problem is that it slows down all wheels equally, making even nearby tokens harder to distinguish.

YaRN's solution is selective interpolation. It divides the RoPE dimensions into three groups based on their wavelengths. Dimensions with very short wavelengths (high frequencies) are not interpolated at all. These fast-rotating "wheels" need to stay fast to preserve the ability to distinguish adjacent tokens. Dimensions with wavelengths longer than the training context are interpolated fully, just like PI. These slow-rotating "wheels" can afford to rotate even slower to accommodate longer contexts. While after interpolation, the network might interpret a relative position of 10000 tokens as, for example, 5000 tokens, they are both very far away context so shouldn't have a huge impact on performance. Finally, dimensions in between get a smooth blend of both strategies.

This way, the network maintains its ability to understand local relationships while gaining the capability to handle much longer contexts. YaRN also introduces a temperature parameter in the attention mechanism that helps maintain consistent performance across the extended context window.

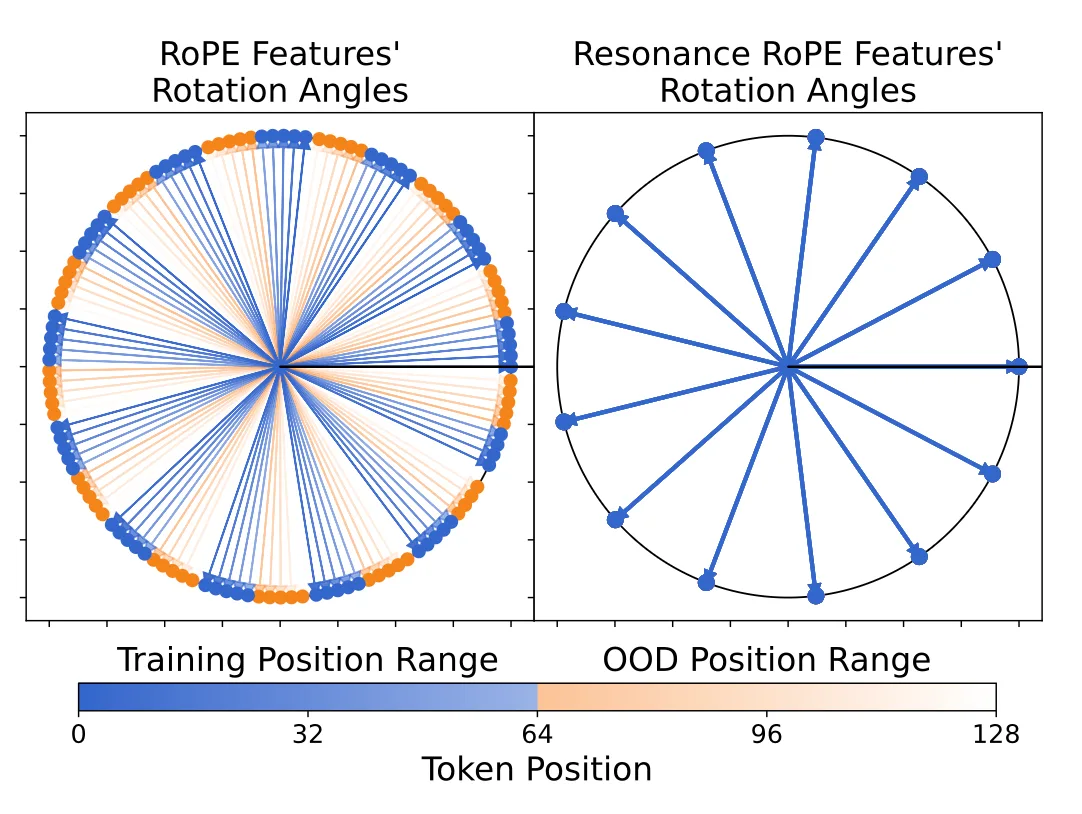

Resonance RoPE

YaRN solves the extrapolation problem by not interpolating the high-frequency dimensions. But there's still an issue even with dimensions YaRN leaves unchanged.

The problem is RoPE's non-integer wavelengths. Because of the common base value 10,000, most dimensions have wavelengths like 6.28 or 15.7 tokens. Back to the odometer analogy: imagine a wheel that rotates every 10.3 positions instead of exactly 10. At position 10.3, it shows the same angle as position 0. At position 20.6, same as position 0 again. But during training on sequences up to length 64, the model only sees positions 0, 10.3, 20.6, 30.9, 41.2, 51.5, 61.8. When inferencing on position 72.1 or 82.4, these are rotation angles the model never encountered during training.

Resonance RoPE addresses this by rounding wavelengths to the nearest integer. A wavelength of 10.3 becomes 10. Now positions 0, 10, 20, 30... all show identical rotation angles. When the model sees position 80 or 120 during inference, these align perfectly with positions seen during training. The model doesn't need to generalize to new rotation angles. This applies to all dimensions with wavelengths shorter than the training length. For these dimensions, Resonance RoPE provably eliminates the feature gap between training and inference positions. The rounding happens offline during model setup, so there's no computational cost.

Resonance RoPE works with any RoPE-based method. Combined with YaRN, it provides a complete solution: YaRN handles the long-wavelength dimensions, Resonance handles the short-wavelength ones. Experiments show the combination consistently outperforms YaRN alone on long-context tasks.

LongRoPE

Both YaRN and Resonance RoPE rely on hand-crafted rules to determine how different dimensions should be scaled. YaRN divides dimensions into three groups with fixed boundaries, and Resonance rounds wavelengths to integers. LongRoPE takes a different approach: instead of manually designing the scaling strategy, it uses evolutionary search to find optimal rescale factors for each dimension automatically.

The search process treats the rescale factors as parameters to optimize. Starting from an initial population of candidates, LongRoPE evaluates each candidate's perplexity on validation data and evolves better solutions over iterations. This automated approach discovered non-uniform scaling patterns that outperform hand-crafted rules, enabling LongRoPE to extend context windows to 2048k tokens (over 2 million).

LongRoPE also introduces a progressive extension strategy. Rather than jumping directly from the training length to the target length, it extends in stages: first from 4k to 256k with evolutionary search, then applies the same factors to reach 2048k. The model only needs 1000 fine-tuning steps at 256k tokens to adapt, making the extension process both effective and efficient. This progressive approach reduces the risk of performance degradation that can occur with aggressive single-step extensions.

References

- RoFormer: Enhanced transformer with Rotary Position Embedding (2024). Su, Jianlin and Ahmed, Murtadha and Lu, Yu and Pan, Shengfeng and Bo, Wen and Liu, Yunfeng.

- Extending context window of large language models via positional interpolation (2023). Chen, Shouyuan and Wong, Sherman and Chen, Liangjian and Tian, Yuandong.

- YaRN: Efficient Context Window Extension of Large Language Models (2023). Peng, Bowen and Quesnelle, Jeffrey and Fan, Honglu and Shippole, Enrico.

- Resonance rope: Improving context length generalization of large language models (2024). Wang, Suyuchen and Kobyzev, Ivan and Lu, Peng and Rezagholizadeh, Mehdi and Liu, Bang.

- LongRoPE: Extending LLM Context Window Beyond 3 Million Tokens (2024). Ding, Yiran and Zhang, Li Lyna and Zhang, Chengruidong and Xu, Yuanyuan and Shang, Ning and Xu, Jiahang and Yang, Fan and Yang, Mao.